I didn’t set out to write a Christmas story. But here’s a present that just landed under my tree. When I published my 2000 interview with roboticist Mark Tilden one year ago (still one of the most popular stories in this newsletter), I asked readers if they knew what had happened to him. Well, the article found its way to Tilden, and a few weeks ago I received a message from the man himself.

A two-hour zoom call to his new personal lab, somewhere in rural Canada, resulted in this new story. In a nutshell, Tilden became Santa Claus, going from the white sands of New Mexico to the toy industry in Hong Kong, then back home to Canada. After selling about 30 million robots and through various dramatic episodes, he’s building again, now moving from toys to tools.

“My goal was the same back then as it is today,” Mark Tilden tells me, “to make robotics better.” He’s speaking to me from his shiny new, 3000-square-foot lab in rural Ontario, Canada. “But how to do that? I always thought there must be simple, elegant ways of building competent machines. Why does nature make it seem so easy, while it takes us so much effort? Look at what conventional robotics has to do just to mimic a fraction of animal abilities!”

Since we last spoke a quarter-century ago, the world has gone from what he calls Terminator-phobia — “The robots are coming!” to a brand new fear—“The robots are coming for your job.” He’s not worried . “My ChatGPT prompt has sat unused for months,” he says.

From tech to toys

“When we met in Los Alamos,” he tells me, “I was spending more time in meetings and writing proposals than actually building. That drove me crazy!” He describes the tortured procurement processes of NASA — “Forty-seven committees just to order nuts and bolts!”

“Hong Kong was an amazing town for a frustrated academic,” he says. He headed there shortly after we met in 2000, invited from someone who owned a toy trading company. “One thing you could do in Hong Kong,” he continues, “if you had a working, viable prototype, you show it, and 30 seconds later you’re in production. How fast can you go?”

This was a sharp contrast with academic science. “Factory prototypes in weeks, production in months, products on the shelves before Christmas.”

“Suddenly,” he exclaims, “you’re Santa Claus.”

Make it for a penny, sell it for a dime

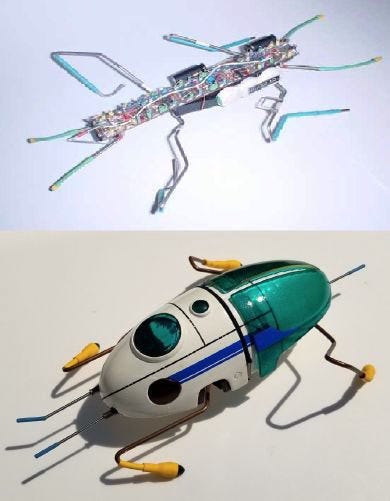

Bio-Bug was the very first product—I bought one for myself when it was released.

“It was based on the biomechs I did at Los Alamos, and years earlier at university. But when you’re building something for an international market, they want to know three things: How to make it for a penny and sell it for a dime, make it available tomorrow, and no risk. Out of all my designs at the time, the basic two-motor BEAM bug design was perfect for this.”

This was because his robots were already based on taking something existing, doing things as simply and minimally as possible.

“The toy industry also tends to deal with technology that is 20 years out of date—for cost, intellectual property, and accessibility reasons. Which was fine for me — I spent many years building from junk.”

I know that he’s continually full of energy—today as much as 25 years ago. And so he was willing to put in the work, even travelling to the factories in China where his robots were being manufactured, overseeing the assembly lines, smoking and napping with the workers.

“We’re talking about facilities more like cities",” he says. “Fifteen-thousand Chinese workers in residence, for example, living on site, six per room. Assembly lines that stretched hundreds of feet, brilliantly set up. One person on one side does the thing, and someone on the other side tests it. Then they play musical chairs until parts-in equal product-out at maximum efficiency. That’s called ‘convergence toward product’. It takes less than five days, even for complex items, and it was amazing to watch, and to supervise.

“I also wound up personally selling and promoting them internationally — living in airports for almost four years ,” he says, “ the first world travelling robot evangelist. Hallelujah.”

“Santa Claus don’t wait”

I ask about the tech behind the first Bio-Bugs—particularly their intelligence.

“Nervous Networks, I called it. Primarily, adaptive Central Pattern Generator oscillators using handfuls of transistors with direct control over drive motors. Best performance-to-silicon I could manage at the time. Still pretty tight!”

“The problem was,” he goes on, “we couldn’t use analog controllers for commercial toys, because we needed sound output and production stability. In Bio-Bugs, we used an off-the-shelf toy microcontroller, programmed to the last available bit. But the original brains were Nervous Net analog control technology. I got very good at duplicating most microcontroller functions with Nervous Net, quickly and cheaply.

“Initially I saw in Hong Kong that you build something that functions, then it disappears into China. And guess what? They might have no idea how it works. But they can duplicate it to their best.

“But with this, they completely failed. If it had been software, they would’ve had no problem duplicating it—they have an infinite number of programmers. But I gave them a big pile of adaptive analog instead.

“So we came up with a technique that was really quite fascinating. They would put my prototypes onto this incredible table with the best digital samplers and scanners. And they repeat and record the patterns the robots make using a drum machine!”

So when it comes to biologically-inspired robots, forget AI.

“I tried to explain Nervous Net systems to them,” he says, “but they didn’t want to know. They only wanted to know, ‘What is the fastest way we can get it to work?’ And for business reasons, that’s exactly right. I had to get out of the academic mindset, and think about what it would take to advance the project forward.”

“See, the main thing about dealing with toys,” he continues, “and something that I really loved, was two rules: First, Santa Claus don’t wait. December 25th — miss it and you’re dead.

“The second rule is: Santa Claus is a bastard. A lot of people come up with one idea and go to Hong Kong, and their idea is rejected for a variety of reasons. You have to apply a shotgun approach to products. I had dozens of working robots, but only Bio-Bugs ticked all the boxes that first year.”

Robo-anthropology

Over the course of 16 years, he moved up from insectoids, through dogs and cats, and on to humanoids, with the first RoboSapiens.

“I had been thinking about minimal humanoids for a long time. And then I literally built the first RoboSapien in a month, at a science conference, while everyone was watching. On the last day, I powered it on, and it sprinted across the table.”

Most battery-powered tech—from toys to Teslas—use energy-intensive electronics that tend to limit their battery life. Unlike any other robot you might get under your tree, RoboSapien would keep you playing until well past Christmas dinner, using standard batteries, so no charging. This was due, again, to Tilden’s bio-inspired philosophy.

“With RoboSapien,” he explains, “every step it takes, 75 percent of the power is regenerated back, using the battery as a superficial capacitor. That’s also the reason it was so fast and fluid — because it’s actively generating power as it walks.

This kind of reflex electromechanics differs from other robotic servo systems, because it uses a natural center of gravity for each particular moving part, then applying that to the entire structure. “Like if you let your wrist go limp,” he says, “your hand will default to a certain position. Apply that to a whole body, and that’s exactly RoboSapien: it’s one-fifth my size, and by default shaped to my proportions—as if I’m floating in a pool.”

It was a huge hit, and resulted in many surprising stories and insights. “For the first time,” he tells me, “I was able to see true, interactive robo-anthropology.

“There’s that crazy guy in Scotland who had 20 RoboSapiens pull him down the street on a skateboard. Other people treated it as a little actor. Because actually, I hoped it would help the camera-shy, by being their little avatar. And it worked like a charm. There are hundreds of RoboSapiens videos floating around the internet, even today.”

“When I watch TV, or YouTube,” he continues, “I always see them on a shelf in the background. The Big Bang Theory, for example — one was there for the entire run of the show. And in various Hollywood movies.”

RoboSapiens sold for about 15 years, right up to the pandemic. “I think we sold 12 million in total,” he recalls. And then, “one day,” he remembers, “one of our salespeople came and said, ‘Dinosaurs.’

“Now, why are robots and dinosaurs some of the biggest staples among all toys?” he asks. “Because one is so far in the future that you’ll never see it, and the other is so far in the past that you’ll never see it. So why don’t we combine the two?

“I went back to an academic paper I wrote around 1992, which talked about the potential resonant structures of a Tyrannosaurus rex — a bipedal dinosaur. His Hong Kong bosses asked how big he wanted to make it. “And I said, ‘Size of box equals size of daddy’s love.’ So we made the things a meter long! And we sold over eight million.”

Again, his innovative two-way power-generating motor control tech served these monsters well, “on just six AA batteries,” he proclaims proudly. “They would run from Christmas right up until it’s time to go back to school in January. We took what we learned from RoboSapiens and applied it across a wide range of items.

“I have a great memory of being chased down a factory hallway by 300 of these dinosaurs, and me with the only remote control that could stop them. Noisy, and actually scary as f*ck!”

In the constant push for new products, what could possibly come next? “I came up with a series of robots that were aliens,” he says, “based on my old Mars rover research. Fun fact: it turns out that Martians never pay for any of the robots we send them. Human parents—different story.”

Perhaps as interesting as the excitement of building and selling at hyper-speed, an unexpected insight came up. “It was interesting to see YouTube emerge not just as a place for advertising, but as a destination for toys — a place to play with them in public, as performance. And for us, as the manufacturer, we got direct evidence of how customers were interfacing with our products.”

Into the Uncanny Valley

Even with his novel analog technology recorded and played back as digital signals, Tilden’s robots still seem to have an aliveness that humans and other animals intuitively respond to. “If you’ve ever tried to run over your dog or cat with a radio-controlled car,” he laughs, “many won’t even look. But back in my Los Alamos days, my giant spiders were never accepted by my friend’s huskies—violently so.

“Think about the Uncanny Valley,” he goes on. “How did it come about that we’re so afraid of something that looks just like us, but not quite? Where in our evolutionary past was there something like that? You gotta wonder, when will the robots cross that boundary?”

For me,” he reflects, “it’s a bit like dealing with farm animals. As long as you’re smarter than they are, be sure you’re the one holding the reins.”

Having conquered the robotic animal market, Tilden shifted gears. “We did well with toys, and someone asked me, ‘When are you gonna build something that’s actually useful?’ So I thought what would every college student want on their side table?”

“You remember those animated Pixar lamps?” he asks “Just like that. Something that didn’t just help you see, but could itself see. My boss came to me and said, ‘We need something that can detect a human being two to three meters away. And it’s got to cost 15 cents.’ No worries boss!

We wanted to sell it not just at Toys ‘R’ Us, but at places like Sears Roebuck, meant for your toolbox. It was a flashlight that followed your hands around — you didn’t need someone to hold the flashlight for you. You could talk to it.”

You’ve seen the first Iron Man film?

“But,” he says, “once again, a really nasty reality came about: You cannot sell toys in the tool aisle. The way our economy is set up, there are toy buyers and there are tool buyers, and never the twain shall meet.”

The jellyfish

That was a minor setback compared to what happened next.

“Hong Kong was great,” he recalls. “I put in 18-hour days, and at night, with all those lights, in the rain, add a Vangelis soundtrack and it was Blade Runner. Considering my profession — appropriate.”

I ask him what happened; in our email exchange, he mentioned something about the Communists setting fire to his office.

“Something even worse happened,” he replies. “In 2015, I went on holiday in Florida, and stepped on a jellyfish on the beach.”

“Oooh, that’s worse,” I say.

“Yes, it was. An MRSA superbug slowly ate my foot from the inside out. I spent a year in a Chinese hospital. Pretty much the end of my career. And my left leg.”

He relates how such an infection wasn’t just restricted to his leg, but affected his thinking. “But,” he brightens up, “my then-girlfriend (now wife) did an amazing thing — quit her job and came all the way to Hong Kong from Canada to get me out of there. I came back, and I was pretty much forced into… an easier lifestyle.”

At the time, he was also working at the Hong Kong Polytech, "which was right next door to where he was working on the toys. “Some colleagues (Ben Goetzel, David Hanson, et al) at the time were building a deterministic AI robotics model, which I think should be pursued further — that’s where the system will give you the same precise answer again and again. As compared to the many stochastic language models now in development.

“Think of the computer on the Starship Enterprise. It always said the same response (with Majel Roddenberry’s voice). Always extremely predictable — because this is what we want in our tools!

“See, something like ChatGPT is a language model, and language is not precise. Are you going to trust a business decision on a ChatGPT maybe-response and possible hallucination? Someone needs to build a ChatGPT scientist, or engineer: the most annoying, pedantic academic you can imagine. That would actually be useful, because it would force some humans to recognize that precision and complexity are vital when you’re poking the edge of physics.”

“Go back to Iron Man,” he says. “Like the computers from Star Trek, a robot like that needs to be much smarter than—but willing to compromise for—its human contemporaries.

“We were getting very close to a lot of that over 10 years ago. Then a jellyfish reminded me of its superiority in the evolutionary hierarchy. Glad it’s dead.”

On to tools

“So, to finish my story, I flew back to Canada in 2017, they amputated my leg, and I’m now partly robotic myself. Which is maybe ironically appropriate.” He started a long healing process, “First to walk. Second, to get my brain back. And recently, to start building again.”

He’s watching the current AI and robotics landscape with interest, “now that plagiaristic language models seem to be hitting a plateau. They’re not the killer app the companies were hoping for.

“It’ll be interesting to see what happens as the tech scales up — completely automated factories and all that. You’ve got a few fully automated grocery stores there, in London,” he notes. “But what happens when they fire all those minimum wage workers, then spend a fortune on the tech, and need highly-paid programmers just to maintain and service the damn thing.”

He wanted to get back to Hong Kong. “But,” he says ominously, “I worry I might be on a list.” And then, I have some pictures off of CNN — of my office on fire. Of the 28 people in our research group, I know of only three who made it out for sure. Not sure what happened to the others. Hope they’re ok.”

Hong Kong in the 2000’s, he recalls, was a dream, but all dreams come to an end. “After the handover from the UK to China in 1997,” he says, “everyone thought it would become like Vancouver with noodles. Alas.”

So now, he’s back in Canada, starting a new lab. But his priorities have shifted firmly away from toys and toward tools.

“The thing is,” he says, “if you build toys, you’re a low-grade entertainer. So now I’m building tools. What kind of thing would people immediately recognize as a useful and valuable robot assistant? I’m testing items right now that I think might actually do significant jobs.”

This doesn't necessarily mean AI and the most advanced tech. His old analog techniques still have legs, as it were.

“Obsolete tech has so much available potential. For example, there’s an amazing toy, worth looking up, called the Hansen 20Q. It’s a little box that guesses what you’re thinking in less than 20 questions. It’s from 1988! That was based on an incredible study by a British professor, who came up with a statistical model based on a range of English-language databases. Worked well, dead cheap, obsolete technology, no risk… Hey, that sounds familiar!

“It was just a database, but if you gave that thing decent speed, sensors, and a body… No matter what you do with AI, it’s always gonna be a brain on the other side of the glass. If you want it to be marketable, give it legs.”

I ask him for advice for any aspiring roboticist.

“Yes. On all beaches, always wear watersocks.

“But also, whatever you make, personally or professionally, choose methods that allow you to build faster than your speed of distraction. And be sure to finish your projects as existence proofs, because nothing is more powerful than repeatable physics that works.

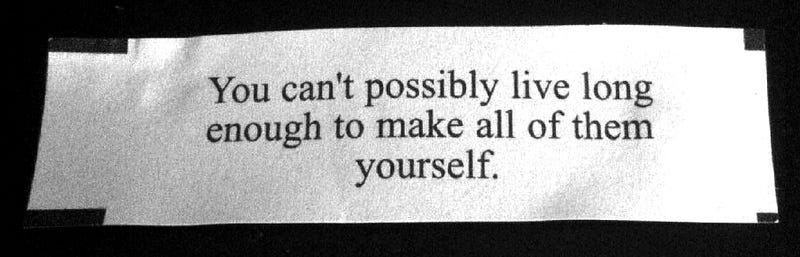

“Hey,” he suddenly remembers, “I got this in a fortune cookie in Hong Kong:”

“We’ll see about that,” he says.

There’s plenty more—read an edited transcript of our entire conversation (complete with technical schematics) here.

I used to know Mark back from the pre-beam days. (MFCF hardware lab)