Seeking uncertainty In technology

What does human creativity look like in an increasingly technological society?

You’ve seen videos of those robot dogs made by Boston Dynamics. Agile, strong, uncanny. Now imagine one circling around you. How would that make you feel?

I ask Cyan D’Anjou about some of the advanced technologies she’s been working with, and the robot dog immediately comes to mind. D’Anjou is an emerging artist on a fast track to international success at age 23, with an incredible background of practical skills and knowledge stretched across art, science and design.

“The robot!” she exclaims. Her enthusiasm and warmth are infectious, her thoughtfulness inspiring. “The dog from Boston Dynamics. It was almost jarring to work with because it really feels like an animal. You know it’s not, but it’s designed to look and act like one.”

“And it really matters where you are,” she goes on, “which side of the controller. We did an experiment where we sat inside of a perimeter and had it walk around us in a loop, as if it was protecting us. And we felt protected.”

“But when someone else was sitting in the center,” she continues, and we changed the verbiage to be like it was observing her, she felt very intimidated. Both times, the operator of the robot was doing exactly the same action.”

“I think that says a lot about the gaze of technology,” she reflects. “And about transparency. It was the first time we had been given access to such a tool – that digital agency, that knowledge that’s withheld from so many people. Knowing what it feels like to operate it. It’s made for military purposes, to go places people can’t, it’s been used to enforce curfews. It’s quite scary what it can do, and at the same time in the form of a dog, so somehow also cute – just like a real dog.”

Chasing cars

Thinking about that gaze of technology, that transparency, I naturally thought of AI. “I think it can be a tool for understanding where we are a little bit better,” D’Anjou tells me.

At first, she shared the widespread concerns about bias in AI systems. But then she heard about a project in rural Brazil, in which streets and buildings were 3D scanned in order to identify where the government should invest in local infrastructure.

“If we look at that dataset,” she says, “it’s highly biased. But it’s incredibly important in context – specific, personal, necessary. What a house is in that community would not apply at all to a house here.”

She took part in an exercise in Austria that involved counting cars. “Well,” she says, “Austria has trams, and these little cars that collect trash. And the model we were using, from Boston, doesn’t recognise those as vehicles. In contexts like that, bias is almost essential. Or rather, context is essential.”

“So AI is interesting in that sense,” she continues. “It can tell us what it’s contextualized to, where its focus is, and isn’t. Then, how do we build more personalized, specific datasets for each context.”

Chasing the un/knowable

This newsletter follows nicely from a recent one about creativity and AI, because D’Anjou’s guiding question has been, as she told me, “What does human creativity look like in an increasingly technological society?”

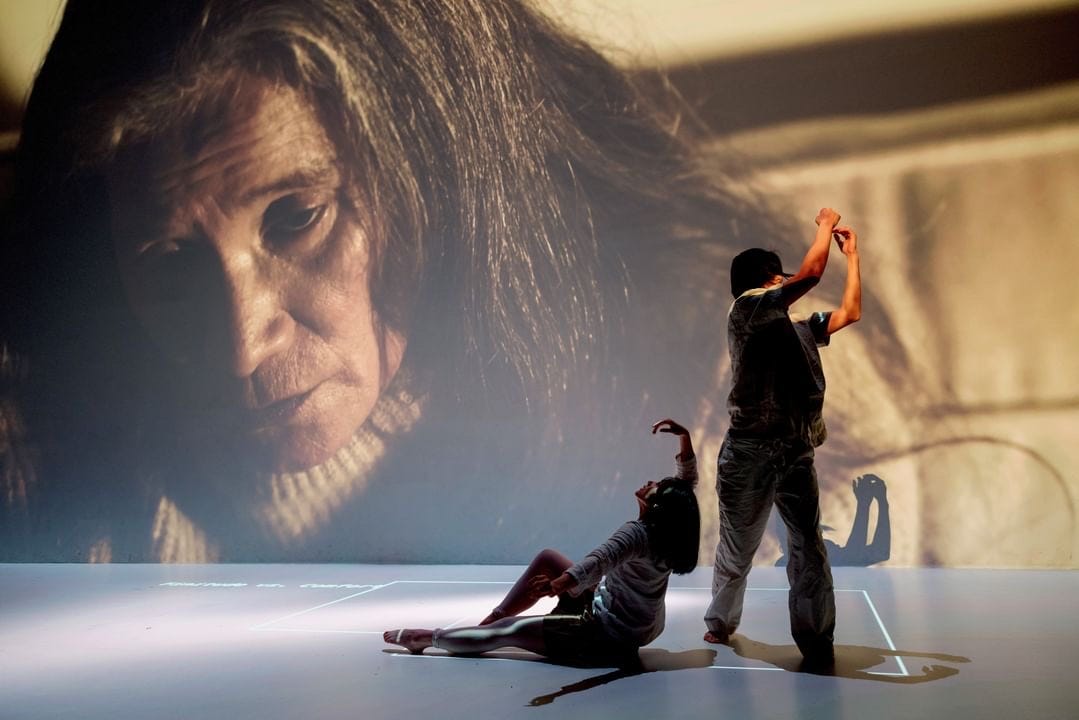

It’s almost eerie, in fact, because previously, researcher Caterina Moruzzi talked about the “unknown unknowns” of creativity, D’Anjou is working on two mirror-image projects, called Knowable Certainty, and Seeking Uncertainty.

The first, a collaboration with PhD student Luisa do Amaral, emerged from the way they both approach their work. “I love figuring things out,” D’Anjou tells me, “researching a question, and then finding out that the answer is just another question, and going from there.”

She acknowledges this is not a traditional approach to art. “I’ve always struggled to see art as a form of self-expression,” she says. “I know that’s therapeutic for some artists. For me it’s easier with research – using texts, documents that capture that emotion that I’m feeling. That’s more therapeutic for me.”

At the same time, Seeking Uncertainty is about exactly that, she says, “wanting to dive into this thing that I can’t know, and seeking acceptance that I can never know some things.”

This hunger for answers, paired with embracing the unknown, reflects a cosmopolitan background. Born in the Netherlands to a family of skilled artists and woodworkers, with roots stretching across to Martinique in the Caribbean, she grew up mostly in the US, designed her own degree at Stanford, and recently completed an MA in London.

Now she’s back with family in the Netherlands, having just participated in Ars Electronica’s Founding Lab, and toured her latest work, Organic Social Capital.

Enter the greenhouse

What does the work look like? As you can imagine, it’s full of contrasts. A greenhouse sits on the pavement in an urban environment, surrounded with plants. But its orange-coloured windows make walking inside like walking into the future, where you’re greeted by a tall, equally orange altar containing 3D-printed plants. A printed manifesto of a corporation declares, “Nature is the most valuable asset we own.”

“It’s a fictional society set in 2045,” she tells me, “where our social status is linked to how much we give back to nature. I took plants from different regions, planted them around London, and also 3D scanned them – the printed ones are on the altar. Then I created a livestream of the real plants. A web app called Organic Social Capital is like a future banking system, where you can interact with the plant of your choosing.”

I point out that this is also eerily similar to the story set in 2041 that I described in the first issue of this newsletter. But in her project, you gain social capital not from voluntary work, but by giving part of yourself over to plants.

“As humans,” D’Anjou says, “we have blood, hair – all these things that have nutrients that plants can use to grow. The idea of self-sacrifice – we usually put into a career. Instead, here it’s fed into a plant growing system – the more you sacrifice, the more credits you get in the system.”

It’s easy to see that this is a provocation, and it led to heated discussions with visitors in Milan, Dubai, and Dutch Design Week, where she engaged in many conversations – with people who were freaked out by the idea, who loved it or were angered by it. That, of course, was the intention. Who should own nature anyway?

Building with boundaries

“I struggle with worldbuilding,” D’Anjou tells me, “because of how many rules it takes to explain a scenario. I want to be able to enter something and immediately find some connection.”

“That’s maybe why I built that big orange table,” she continues. “Even though it represents something in that world, I also want it to be something that someone could align their own experience with. Maybe my personal experience isn’t unique. Taking myself out of the work to some degree doesn’t mean it’s not about me. Maybe one of my skills is to express it in a way that is about something broader, that other people can insert themselves into.”

We talked a lot about the artistic process. I related how my students often got lost in research, then struggled to try and fit it all into the work. “I was just talking about that yesterday,” she replies. “Luisa’s output from our project is a research paper, so the first couple of months we just dove into her references, reading them to better understand different perspectives.”

“But because we were so deep in that process,” she goes on, “it felt like that was the work itself. And I found it really hard to do it justice – how do I make something worthy of all this time we put into research?”

One approach, I suggested, was letting go of the research and just making something every day, without overthinking – the ideas should naturally come out. “What was so helpful for me,” she counters, “was just making something fast.”

This played out at Founding Lab (where she encountered the robot dog). “We did this project using a drone, within two hours,” she recalled. “Here’s a drone, here’s the software, you have two hours to come up with something, and show it.”

The drone, for them, became the sun, rising and falling in time, which they all orbited around like a maypole. “We knew how to work the thing, so we could go wild with the ideas,” she says. “It was so rewarding to have a small amount of time, and make something that all of us were really proud of.

Provenance & prototyping

It helps in such rapid prototyping to have the skills and knowledge about how to make things. These she gained growing up, from her uncle, grandfather, and other family members.

“Oh yeah,” she lights up. “The biggest thing is that anything can be made. Anything. In fact, anything can be made in three days!” She laughs, referring to the orange greenhouse.

“When I was planning it,” she says, “I thought, ‘What if it had these floating spheres’. Crazy stuff. But the thing is, things might be hard, but there’s nothing you can come up with that’s impossible. What’s nice about [my family] is that they know how to make it possible. Being in that environment is ideal. Growing up, I had a sense that anything was possible.”

Related to this is knowing where things come from.

“I visited a steel factory a couple weeks ago,” she tells me, “as part of a field trip we did in Austria. They make the little buckles on shoes – the things that shoelaces go into. Such a small item. But knowing how things are made – the whole process – is knowledge that not that many people have access to. Knowing where every part of something comes from.

“Gaining that knowledge, you feel a sense of responsibility, knowing where things in your environment come from, how they’re made, how they got there.”

Like operating a drone, or a robotic dog, or knowing where the data in an AI system comes from. It’s the guiding idea behind this newsletter, and my whole career – putting advanced technologies into the hands of artists like Cyan D’Anjou. Let’s see what she gets her hands on next.

Want more? Read a complete transcript of our interview here.

If you like this article, you can subscribe for free: I aim for a 15 minute read once a week.