Do you talk to your phone? AI makes actual conversations increasingly possible. But what if we were to look at everyday, nondigital objects as having some kind of computational power?

It turns out there’s a long history of this idea. This article is about “object-oriented programming” in the real world. I show how we can take computing concepts out of the box and off the screen, look at some of the ideas behind objects as active agents, and the social implications of this.

De-computing the world

A lot of my academic career has been devoted to bringing computation to physical objects on the one hand, and bringing computational ideas into the nondigital world on the other.

The first idea is widespread – “Internet of Things.” But the second sounds crazy: why think like a computer in a world that’s messy and nonlinear?

One answer is to bring control, predictability and order to complex systems and spaces. But I like to embrace chance, randomness and the messiness and absurdity of the world. When I was teaching in an art school, we wanted to find an alternative to trendy “design thinking” that aims to solve problems and produce commercial products. We wanted to use making, not thinking. And we wanted to raise questions instead of trying to solve problems, since, arguably, “design” broadly defined has in fact created many more problems than it has solved.

An unlikely answer was to turn to computers. Taking off from the idea of programming the real world, I called it “de-computation”. That means, perhaps, subtracting computational technology from the real world. But at the same time, embracing the computational capabilities of nondigital objects and environments. So, computational thinking combined with design making.

There’s some science behind the world being a naturally computational place. Biologists already embrace the idea that information (for example in genes) is fundamental to life. Some even propose that the origins of life are algorithmic in nature. Some physicists envision the entire universe as a computer.

It’s easy to see such thinking as technological determinism – the way that, in the Renaissance, the universe was viewed as a mechanical clock – the most advanced technology of that time. But let’s stick with it for the moment and see if computation offers anything useful for thinking about the real world.

Back to basics

Thinking about object-oriented programming, broadly defined, we should define some basic terms.

First, what is computation? I like Heinz Foerster’s definition: “computing (from com-putare) literally means to reflect, to contemplate (putare) things in concert (com-), without any explicit reference to numerical quantities.” He defines computation as “any operation, not necessarily numerical, that transforms, modifies, re-arranges, or orders observed physical entities, ‘objects’ or their representations, ‘symbols’.”

This fits with with my approach – to consider computing without computers. One computer scientist said, “Computer Science is no more about computers than astronomy is about telescopes.”

What is an object?

If we refer back to René Descartes (“I think, therefore I am”, separation of mind and body), everything outside your mind is an object; you’re the subject. This is a semantic definition: everything you regard is an object of study. This neatly echoes Foerster’s distinction between objects as physical entities and their representations, which can live inside our heads.

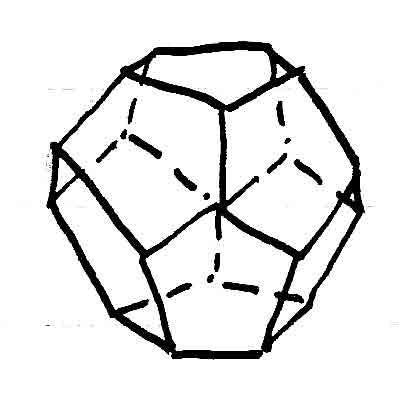

Let’s take a computational definition of an object: “a tangible entity that exhibits some well-defined behavior”. It has certain properties (size, shape etc), so it contains data that enables us to interrogate its current state. And if it exhibits “some well-defined behavior,” this implies that it does something, it can execute some procedures or perform some sort of computation. This definition comes from this excellent introduction to object-oriented programming by Grady Booch and co-authors.

Things remember what people forget

Okay, we can agree that an object has properties like its size and shape. But what about that part about behavior, about executing procedures or doing some computation? If an object is just sitting on a shelf, is it actually doing anything?

Let’s look at the most basic case: an object is there or it’s not. If it’s there, something is different. This relates partly to appearance: that golden ceramic cat on my bookcase undoubtedly enhances the aesthetic of the room (in my opinion).

If something is there, in a very simple sense, it does something: it generates a representation in my head. Maybe it triggers a memory or a connection to something else. Every time I look at that ceramic cat, I think of Jack, that really annoying live cat I had at the time I found the ceramic one on the street.

Things remember what people forget. The Iriquois, like many cultures, use objects as mnemonic devices, for sharing and passing down stories and traditions.

The sociologist William Whyte found something slightly different. In his excellent film The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces, he shows how a provocative sculpture placed in a city plaza prompted spontaneous discussions between strangers. That object did something through its mere presence.

Using objects to aid memory has a very long tradition – dating back at least to Ancient Greece, in the technique of the memory palace or memory theater. (I discuss that here.)

There is a more precise definition of what objects do, from physics: every body, every atom has mass – and that means it exerts some gravitational pull, no matter how small. In the case of Jack, some sort of weird gravity held me within this cat’s orbit for close to 20 years. But that’s something else; let’s not get into emotional connections.

But Jack’s presence – now absence – raises another point (no, nothing to do with Schrödinger’s Cat). What happens when an object appears or disappears? If you’ve been around small children, one of the first games they like to play is peek-a-boo: you can see the irrational joy they get when you alternately hide and show yourself or some object.

The developmental psychologist Jean Piaget studied this, and noticed that kids less than around eight months old seem to believe that when you hide something, it’s gone forever – they won’t look for it. At around eight months, they start to look for it. This learned behavior is called counterfactual reasoning. (This is discussed in more detail here – sorry, paywall.)

Methods of intent

So now I’ve given you evidence for what objects can do to people, without actually doing anything except existing. They have some functionality, in computational terms. Let’s explore this functionality a bit further.

In JavaScript for example, digital objects are containers for properties (their attributes) and methods (functions). Their properties remain consistent over time, enabling us to classify them into categories. Each individual property, however, can vary. My golden cat has a property we could call “shininess”, but I would characterise it as not completely shiny; if I had to quantify that property I might give it 60 out of 100. Jack had the property of “annoyingness”, and I would rate that 100.

An object’s methods can be invoked (called) at different times. What exactly are these methods? Recall Foerster’s definition of computation: “any operation, not necessarily numerical, that transforms, modifies, re-arranges, or orders observed physical entities, ‘objects’ or their representations, ‘symbols’.” So methods can include transformation, modification, rearrangement, or ordering.

For example, if I wanted to transform my golden cat into a golden rabbit, I could start by extending its ears, perhaps using clay. (This strange example comes to mind because my brother actually created such a cat/rabbit.) I could simulate that in the computer before the messy, resource-intensive real-world work, to see how it might look.

This is what object-oriented technology was developed for. It’s a way of managing complexity and building systems for the real world.

I say object-oriented technology because it’s not only a form of programming, but can be used to analyse existing objects or design new ones. To do that, you first extract or define the data (attributes) and functions of a (real or imagined) object. What kind of data could be input and output, and how? What does it do, what do you want it to do? Then you draw, diagram, plan (for example using pseudo code) and simulate (for example in Wizard of Oz-style).

Cat class

Because my golden cat has only some essential features of “catness”, it acts as a kind of symbol to represent all cats. That is, the class or category of cats in general. The shape of the golden cat still reminds me of Jack, who was black and white.

Scott McCloud brilliantly illustrates this in his must-have book Understanding Comics (hint - it’s not just about comics). He shows, visually, how a detailed drawing of a person’s face represents only one single individual, but the more you remove details – to the point where it’s a smiley with two dots and a line – it comes to represent the class of all people.

The idea of abstracting the qualities of things in order to put them into categories is exactly what contemporary AI systems do. Classification involves discrimination (between classes), and hierarchy: Jack belongs to the class of black-and-white cats, which in turn belongs to the class of all cats.

Booch et al illustrate this hierarchy humorously with a cartoon of a group of architects designing a “Trojan Cat Building,” each architect working on a particular component: the “bird aggravation system”, “purring system” and so on.

Classification is also inherently subjective. The authors illustrate this nicely with another cartoon, of a cat which is observed by a veterinarian and (what I would classify as) a granny. The vet looks at the cat and sees its anatomy; the granny sees a ball of fur that purrs.

Whoever creates the categories, they allow us to consider objects as part of classes. In the computer this means that if you define a class of objects, you can magically create many instances of an object of a particular class, and each of those objects might have the same properties but vary in how they express those properties. Instances of the class “cat” with the property “color” could be golden or black-and-white or whatever colour.

Objects in action

We’ve seen how objects have properties and functions, how they can be abstracted into classes. Now let’s look at how we can actually use them for programming.

Booch et al “view the world as a set of autonomous agents that collaborate to perform some higher-level behavior.” Objects, they write, “collaborate to achieve some higher order outcome.”

How do objects collaborate? Through instructions and communication. A program is defined as a sequence of operations – instructions arranged like a recipe. (Computing is defined nicely here.) You can look at this as a sort of theatrical staging or choreography.

We could say that a program, as a set of instructions, is a special class of the larger class of languages – a language that can be “run” to do something. It translates theory into practice and affects things in the (digital or physical) world. Some linguists argue that all language is capable of prompting action, through “speech acts”.

What sorts of instructions or operations can objects carry out? Here are a few examples, from the Processing programming environment:

Boolean operations: Boolean logic (check Wikipedia on George Boole and his ideas – super interesting) is a binary choice, typically a value which is true or false; numerically, one or zero. In the real world (especially at the quantum level), the question of what is true or false, fact or fiction, becomes fuzzy. Fake news anyone?

If/then: allows a program to make a decision. I said above that a program is a sequence, implying a linear sequence; this sort of branching algorithm enables it to go in different directions, or to jump to somewhere else then return. If x then y: in the real world, it becomes a general life question.

createImage(): In Processing, this creates an image object (a container for storing digital images). “This provides a fresh buffer of pixels to play with,” says the reference for this command. Here we can consider a scene to be a collection of points in space and time to be played with. What does this mean off of the screen?

Save: in Processing, this command lets you save an image from the environment (display window) to your device. Here we could make an analogy with a museum visitor taking a picture - thinking computationally would mean describing the actions, format, and display area of the image to be captured. Framing becomes a subjective issue.

Objects’ performance and collaboration takes place in some physical context – an environment, whether digital as in a computer simulation, or real as in a museum exhibition. Theater is a good analogy: in a museum, people shuffle past fixed objects, whereas in a theater, the people are fixed and the moves across the stage. (Memory theater actually inverts this.)

As well as within a spatial context, programming takes place over time – the term “processing” contains the word “process”. In computation, time as applied to objects can be separated into states and events – one being more persistent, the other punctuated. This also works in the real world – for example observing the behaviour of people (example here).

The essence of objects

So far I’ve taken some concepts from computer programming and applied them to the real world, to show that objects can be shown to have more agency than we traditionally give them. Now I will zoom out to look at a few ideas from philosophy, in order to interrogate this supposed agency, and see how useful and applicable it might be as a way of thinking and acting.

First, let’s return to the notion of classification. Booch et al abstract an object’s “essential behaviour” in order to classify it. Viewing the essence of things, instead of their mere existence, becomes a metaphysical question. It’s one thing to say the golden cat exists or doesn’t; it’s another to classify it as either golden or a cat.

This points to the power (or failure) of language. Its very nature, and usefulness, is to classify things and communicate through shared meanings. But again, classification is subjective. Is a static ceramic thing really a “cat”? What about one with rabbit ears?

Secret agents

If we push back against the hegemony of human language and classification, we might start to regard objects as more equal to people. Consider, for example, how some “natural” things such as forests, and some “artificial” ones such as companies, have secured legal rights as individuals (while recognising that the distinction between natural and artificial is itself a binary classification, and a problematic one when you look at it closely).

A world where the human is de-centered and placed on equal terms with nonhuman things is called, in philosophy, a flat ontology, or in a more specific version, object-oriented ontology.

It’s important to add that bestowing agency onto nonhuman things is not only done by Western academic philosophers, but is part of many cultural traditions. Some cultures in the Amazon River basin, for example, view animals, rocks and weather systems as completely human (more specifically, those things see themselves as human – Eduardo Viveiros de Castro discusses this). This way of thinking is generally termed animist, as in, an object is animated from within – it has a soul, spirit or other life force. (For more see this article.)

The implication of this line of thought, according to anthropologist Tim Ingold, is that “if agency is imaginatively bestowed on things, then they can start acting like people. They can ‘act back’, inducing persons in their vicinity to do what they otherwise might not.” He prefers to locate the agency of objects not in a spirit or soul – for that is something we impose or imagine – but as something that arises from their material properties.

Consider the quasi-object described by philosopher Michel Serres – a lump of dough for example: not quite solid or liquid, constantly changing its shape, each point in its topology changing position, it becomes an object-event (to use a term from another philosopher, Gilles Deleuze).

Such objects, according to curator Noam Segal, “function as a mediator between us and the world: They act for us, on behalf of us, incorporating and transmitting our agency, almost as extensions of humans. Serres considered the iPhone such a quasi-object, and lustfully, it is.”

There are no things

What if we take this idea further to say that the relations between things, or their interactions over time, are all there is. Sounds crazy, but again at the quantum level this appears to be the case: the physicist Niels Bohr believed that what we think of as an object (an atom in his case) is actually a property of observed interactions between entities with no fixed position: down there, it’s constant movement.

If we take that at face value, this means that every “thing” in the world – living or not – is made of smaller things in constant motion. Nothing is fixed, everything is temporary and in constant flux: even the most stable things we might think of (rocks for example) emerge and break down over some timescale.

What’s more, biology tells us that humans are made up of more nonhuman microbes than uniquely human ones. Each of us is not, therefore, a single individual.

So maybe we should go even further, and forget objects altogether. That was what J.J. Gibson proposed. He was an environmental psychologist, and urged us to look instead at surfaces, substances and medium. What we call a “detached object,” he writes, “refers to a layout of surfaces completely surrounded by the medium. It is the inverse of a complete enclosure. The surfaces of a detached object all face outward, not inward.”

The implication of his approach is that, when we consider an object in motion, this “is always a change in the overall surface layout, a change in the shape of the environment in some sense.” Recall that point above about how objects affect their environment: he takes this quite literally. (Fuller discussion about Gibson here.)

The political life of the object

In art from the 1960s onward, there actually was a sort of dissolution of the object: curator Jack Burnham looked instead to systems, and Lucy Lippard chronicled the de-materialization of the object in favour of the situation.

I believe that artists are always a step ahead of everyone else (even if they don’t always articulate their ideas in rational ways). And this points to a broader shift of focus from objects to subjects. It’s the most obvious dichotomy in the English language, but often overlooked: where there are objects, there must be subjects.

I discussed subjectivity, and we could look at its mirror-image, objectification. Politically speaking, that’s been applied to a wide range of human subjects. It implies treating humans as passive objects. If we flip that around, and assign some agency to objects, maybe they then become subjects. Cue Alexa, Siri and their growing cohort of AI actors.

Let’s zoom out further and look again at programming. It’s overly simplistic to say that technology is programming people, because we don’t want to objectify people as passive containers of attributes and functions; and conversely, “technology” never stands alone monolithically – there are always human subject behind it: its agency is indeed distributed.

Then we return to the idea of classification. Politically speaking, class means social class. Sergei Tetryakov was a politically-engaged scientist in pre-World War II Russia, and in his Biography of the Object, an object is the narrator, describing its life-cycle, how it was produced, and social relations underlying such production.

Flipping things around, then, could reveal some things that we take for granted. Another example is philosopher Jean Baudrillard’s The System of Objects, in which he poses that we define our identities and social hierarchies through the objects we purchase. It’s a network of interconnected objects create a structured environment influencing human behavior and desires. Objectification indeed.

Things to think with

I acknowledge these critical perspectives about objects, systems, agency and subjectivity. I even agree with many of them. But I do still think the notion of the object has value: as a binary opposition, the subject-object dichotomy exposes a certain mindset behind it. And in that sense, objects – any object – becomes, like an aide-de-memoire or like William Whyte’s sculpture in urban space, a focal point for consideration and discussion.

This is why I like applying computational ideas to the world outside the computer: not to literally program people or spaces or objects in an instrumental way, but to expose the thinking that goes into the box.

Symbols are more precise than words for describing objects. But when complete logic meets humans and other nonlinear systems, randomness and absurdity results.

And we might want to preserve some mystery about what’s inside the computer, the AI system – or any object.

Have you ever seen a “Mexican jumping bean”? It quixotically moves on its own. When the Surrealist poet André Breton was first shown one, he came up with many – often fanciful – explanations. When “the truth” was finally explained to him, it was depressing. Once you discover such a mechanism, you shut down all other possibilities, including poetic ones.

In the age of AI and existential crisis, I hope there’s still a place for wonder, curiosity, and the “defamiliarisation” that the Surrealists and other artists do so well.

Want more? Read a longer version of this article here.