Three problems with time

If greater productivity is your goal, you're facing the wrong direction.

Time is something that everyone knows, but no one can really explain. Physicists and philosophers have found no evidence that it exists at all. Yet the clocks keep on ticking, and most of us treat time as a resource that we never have enough of: as the saying goes, time is money.

It’s easy to know what the time is. You just look at your phone, right? Maybe your “smart” wristwatch. Your device, in any case. The numbers tell all, at a glance and with precision you can trust — how long you’ve got until your next meeting, or how much is left of your work day or school day.

Where do those numbers come from? What do they represent? How do they make us feel? And what are they doing to us?

Just asking such questions implies that something is wrong with time as we know it. That’s indeed what we believe. Artist/researcher Helga Schmid is the world’s leading expert in uchronia — utopia for time. She and I have been studying this for a while now, and this article discusses some of the evidence we’ve collected, then suggests what we might do about it.

Why productivity is the wrong target

You know the feeling. You look up from the screen thinking, Where did the time go? We now know the answer: the computer stole human time. The email inbox, the Slack channel, the social media feeds, the To Do list — they all call out to us, and it’s so easy to do just one more thing. Anyone who works primarily at a screen might feel lucky not to have to shuffle paper around, to get up and over to a telephone cabled to the wall, or go and talk to someone in the next room when an instant message is so much faster.

Yes, “productivity tools” like the computer free up time, as do tools of convenience like cars and dishwashers. One problem, however, is that the time they free up, we just fill with more work. That’s the definition of a gain in productivity — more work done in the same amount of time. Sociologist Hartmut Rosa calls this the circle of acceleration: Technological acceleration leads to accelerating social change, which leads to a broader acceleration in the pace of life, which leads to technological acceleration, ad infinitum.

But when we demonstrate that we can do more in the same amount of time, more becomes expected — by ourselves or our employers. And more, and more. Now we can automate more and more tasks using artificial intelligence, which accelerates the pace of work even more. But now we also increasingly compete with algorithms, robots and AI in an expanding number of areas of work, and they don’t work at human timescales. Instead, the opposite is true: we increasingly work at algorithmic timescales.

Meanwhile, we’re still contracted by our employers for a certain number of hours, maybe even working more than those allotted, if that’s part of the company culture. So we work too much, either by choice or through social or competitive pressure.

Thus as sociologist Judy Wajcman shows, even while leisure time has measurably increased over the past several decades, more and more people feel “pressed for time,” unable to keep up. The number of people diagnosed with “Burnout Syndrome” in Western societies has been rising, according to chronobiologists.

There is now a mountain of careful research showing that people who experience long hours of work have serious health consequences,” according to Stanford Professor John Pencavel. There are strong links between long working hours and smoking, alcohol and substance use. People who work nonstop in fast-paced environments see their bodies start to break down after four years on the job: heart problems, high blood pressure, a greater likelihood of injuries on the job, and poor sleep at home. (source)

Poor sleep in turn creates its own problems. Sleep loss not only reduces cognitive performance and problem-solving ability; chronic sleep loss causes brain damage, specifically affecting our estimation of risk — it leads to more risk-taking behaviour. And the most sleep-deprived are those who like to boast about how little they sleep — leaders of companies, politicians, doctors. These are the people making decisions for the rest of us, notes anthropologist Kevin Birth.

Alarm bells

Okay, we could all work less and sleep more, but what does all of that have to do with the clock?

The second problem arises when we adhere to rigid clock times and ignore our bodily rhythms and signs of trouble. For example, simply using an alarm clock regularly can mean not only depriving yourself of sleep (side note: it’s not possible to sleep too much, according to chronobiologist Till Roenneberg), but also waking up at the wrong time, biologically. Since the body cycles through three to five cycles of shallow and deep sleep per night on average, and each night can vary, your alarm could go off during a deep sleep phase. You know the feeling — that’s when you hit the snooze button and fall instantly back to sleep.

“Sure, I’d love to sleep as long as I want, but I’ll lose my job.”

There are a few ways to address this one. Easiest is to simply train yourself by going to bed earlier (see Roenneberg or Russell Foster on entrainment). The second is to use daylight if you can, to wake up with the sun instead of blocking out daylight, if this works with your schedule. The third is a technological solution: there are sleep tracking apps that sense your sleep patterns using motion or sound, then wake you up closest to your alarm-set time but in a shallow sleep phase. (The downside of such apps, however, is that they can create anxiety.)

This raises an important point: we do not suggest abandoning all technologies and retreating into some fictional past consisting only of natural rhythms. We can use our technologies “smarter” (to use the jargon shared by both the self-help and tech industries).

We can even do this without any reference to clock times. Let’s say we’re going to meet. We agree on a general place and a day — “in the afternoon,” say. Then we use our phones to coordinate: “I’m on my way,” “I just arrived,” “I’m at the cafe” etc. We can do all this without reference to clock times. (This is described as approximeeting by Rich Ling.)

Speaking of self-help, we have identified a big problem with most self-help books and gurus — and with most productivity, mindfulness and scheduling apps. They usually rely on clock times or precise timings. For us, these are part of the problem, not the solution. The common assumption that time is something external and universal means that when people have problems with time, the answer is usually to recalibrate ourselves to clock time, through “time management” and self-discipline, according to Sarah Sharma.

As an alternative, personally I structure my time around tasks and not the clock (whenever possible). For example, instead of scheduling an hour of “focused time” without distractions, I will work on one thing up to a natural stopping point: read or write an article or a chapter, write some code that accomplishes just one thing as part of a larger project, complete some self-contained part of an artwork, etc.

Enter the computer

In fact, we all already live inside an interconnected, global computational system that affects even those remote humans who still might live without any digital technology whatsoever, because this system now affects weather and climate, and by extension food systems, trade, travel and communications.

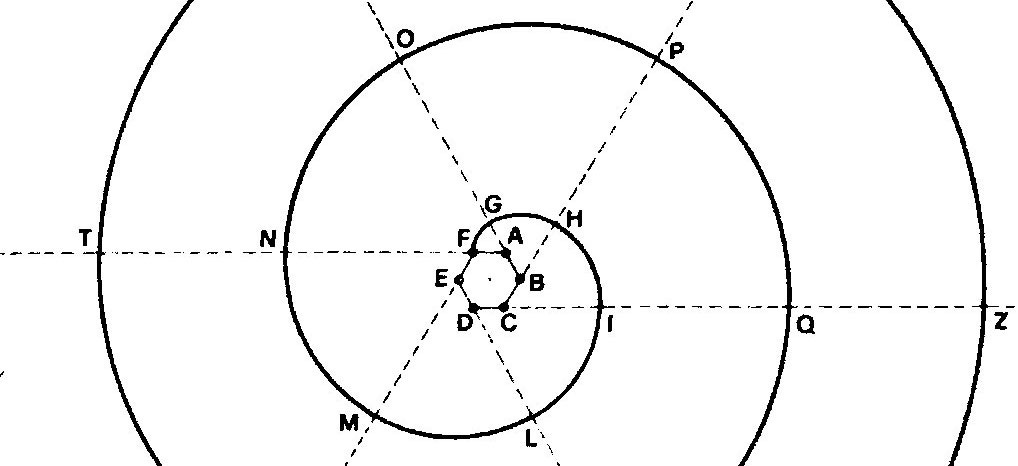

An audibly ticking clock these days sounds quaint, mechanical, even slow — this exposes its origin as a Medieval technology, from which it is basically unchanged. We might well wonder how it lasted so long.

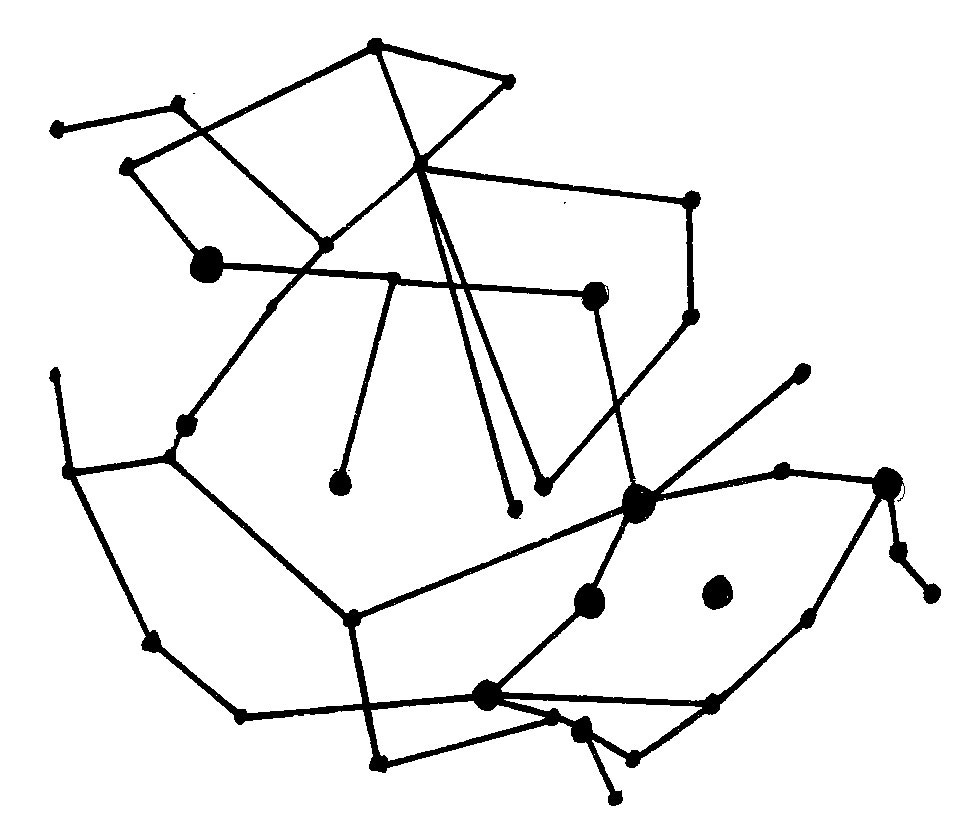

Computational time, by contrast, is silent but produces more anxiety. It is independent of both nature and the individual, subjective experience of duration. In the computer, there are only events and states, as I mentioned in a recent article.

The rhythm of a ticking clock is not far from the human heartbeat. The hour, the minute, the second, even the tenth of a second — these are all perceptible in human terms.

Not so with computime: Just snapping your fingers takes half a million microseconds, whereas in AI systems, decisions that might have broad social implications now take place in a temporal space that’s below the threshold of human consciousness, according to Rifkin. That’s okay to some extent, because the computer can slow things down to human speeds — for example, ChatGPT can generate responses at lightning speed, but “types” them on the screen slowly, for user-friendliness.

The computer also enables microsecond-level precision in the temporal analysis and structuring of human behaviour — for example recording keystrokes and eye movements. Sensors in smartphones impact their users today in, for example, those productivity, mindfulness and health-tracking apps. Many people find these useful, but they reflect not only the quantification of the self, but of time as well: more than just numbers, time becomes programmable. And by extension, so do people.

As Stamatia Portanova observes:

How time is mapped and manipulated by informational machines is clearly an important component of how different experiences of time are brought together and how they are compressed, and it seems evident that our experiences are more and more aligned to their temporal operations.

This is a significant shift. Clocks have structured and synchronized human activity for centuries, and while this caused many problems, people generally accepted and adopted a common timekeeping system that was consistent across all cultures and time zones, for the tradeoff of coordinating their systems and interactions.

Digital computers, too, bring many benefits which are shared by people of many cultures. Like clocks, they are based on mathematical systems originally developed in the Middle East: ancient Egyptians are believed to be the first to divide the day into 24 hours, and the algorithm is derived from Persian mathematician al-Khwarizmi. Like clocks too, computers were then developed into their current form first in Europe, and then headed west to Silicon Valley.

There, computation became a commodity. And because it swallowed clocks and regurgitated them in new, precise and programmable forms, time too became privatized. This is what we mean when we say that we all live in Silicon Valley now: it controls how computers use time, and how both computers and time use humans in turn. Our third problem with time, therefore, is not individual but social.

Computational logic

Sociologist Helga Nowotny shows how scientific time became societal time through technological objects like clocks, computers and mobile phones. These objects, she observes, offer us availability but also demand it from us, creating a mutual interdependence. Furthermore, they dictate particular forms of work, of knowledge, abilities, attitudes and behaviour, and these then become internalised — by both the technological objects and the people who use them.

Let’s be careful not to veer into technological determinism. As stated above, we try to see humans from the perspective of nonhuman objects like phones and computers, but this is only to look back at ourselves.

What’s more, while things like computers might “want” things that serve their own interests, we don’t believe that digital technologies (including AI) can stand alone as independent agents that can be compared with or opposed to humans: these are socio-technical systems. While they might run autonomously in some limited circumstances, they always rely on humans and cannot exist without them. Any “agency” of the computer ends at its source of electricity: you can always pull the plug. Computers’ “own interests” come from the people who make and control them — though these interests might indeed differ from the interests of people who buy and use them.

Furthermore, as socio-technical systems, computers are inevitably tied up with politics and economics.

For example, perhaps the “prime” example of the privatisation of time is embodied by Amazon (itself a socio-technical system). In order to continually accelerate the time it can deliver all kinds of goods, it relies on precise algorithmic tracking of its workers. It’s not the only company to do this: A 2014 lawsuit against McDonald’s restaurants detailed how algorithmic predictions led to abrupt hiring and firing of workers.

It’s easy to be shocked hearing about such “inhuman” practices, but this is rooted in the computational logic of our societies.

Acceleration or atomization?

What happens when we combine the three problems with clock time that we identified — overworking, the individual effects of relying on clock time over natural rhythms, and the social consequences of the algorithmic control of time?

Besides the obvious consequences to individual mental and physical health mentioned above, we can identify some societal consequences — especially when we add in ceaseless social media and constant attention to the screen.

For one thing, we can identify what Jonathan Crary pinpoints as a standardization or colonization of individual experience: “Because one’s bank account and one’s friendships can now be managed through identical machinic operations and gestures, there is a growing homogenization of what used to be entirely unrelated areas of experience.”

Relatedly, part of our unending “work” becomes what he calls self-fashioning, whether through social pressure or an individual desire to get ahead. This work is done on the screen at any hour, “and we dutifully comply with the prescription continually to reinvent ourselves and manage our intricate identities.”

We project our digital selves outwards, and what we get back, at all hours of the day and night, is a constant stream of events and other people’s shifting identities. Context and distance disappear as all things occur simultaneously. Philosopher Henri Lefebvre already noticed this happening with pre-digital 24-hour TV and radio: “The media day fragments. As a result, at every moment, there is a choice.”

But now, because this media of constant choice, continual events and shifting identities is in our hand and in front of our eyes at all times, it’s not only the “media day” that fragments, but time in general. Here comes another philosopher, Byung-Chul Han:

There are no stable social rhythms to unburden the individual’s temporal economy. Not everyone is capable of defining their own time. The increasing plurality of temporal sequences irritates the individual human being and asks too much of it. The lack of pre-given temporal structures does not lead to an increase in freedom, but to a lack of orientation. (p.32)

Han sees not acceleration, but atomization of time. Acceleration, he says, implies a trajectory, a direction; and these, he says, have disappeared. Clock-based productivity apps and constant social media encourage us to jump from one thing to another, destroying any experience of continuity. “This,” he writes, “makes the world untimely. The present is reduced to the point of actuality. It no longer lasts.”

Acceleration or atomization, the full impact of all this on human consciousness is still not known. And so far, according to writer and poet Marianne Shaneen, any open dialogues are neglected,

…including ones such as the value of adopting precision temporal infrastructures in everyday life, the mismatch between the needs of precision time users and many aspects of our social lives, how various social values might contrast with the values embedded in the development of such infrastructures, and, indeed, how time could be designed differently to speak to these issues.

Our common-sense notions of time as fixed, uniform, universal, and external to us, go unquestioned. We couldn’t possible abandon clock time — how could we synchronize our activities and our devices? This is why, when we have problems with time therefore, we generally try to recalibrate ourselves to the clock.

At the start of this article I mentioned a research project in the humanities that pointed to a lack of a common vocabulary for talking about time, and a reluctance (or ignorance) to question the clock. “Our temporal imaginary,” the researchers conclude, “where time is seen as universal rather than infrastructural, is ripe for challenge.”

Challenge accepted.

Want more? You can read a longer version of this article here, with links to some of our projects. In future articles we’ll detail more of our findings and recommendations.