Giving time

Experiments outside of clock time

Cat owners: you know that they’re living the good life, right? Sleep when you like, command attention from your human, come and go whenever, lounge wherever you please. Make no mistake: we all know who domesticated who. (There’s even scientific evidence for cat mind control).

Sounds great, until you actually try to live a cat’s life.

Helga Schmid asked her students to choose alternatives to clock time, then try living their lives to the rhythms of their chosen time-giver for a few days. For most, this was liberating. In Schmid’s experiments, participants often don’t want to go back to clock time afterwards.

But the cat was different. The student who chose to structure her days according to her cat’s rhythms and activities quickly realized her error. If you’re a cat owner, you already know that they’re nocturnal creatures, while most of us are active during the day. The student also discovered that cats eat for about a few minutes, then stare at the wall for hours. Cat naps. More staring. What seemed like a fun few days turned into a struggle for sanity and survival.

It neatly confirms the hypothesis of philosopher Thomas Nagel, in his famous article “What is it like to be a bat?” By which he means, not to imagine how a bat perceives the world. But to actually be a bat. That was just a thought experiment (favorite method of philosophers), not one enacted in real life. In either case, though — cat or bat — the answer of course is that we can never really know. They’re fundamentally different creatures.

We can, however, live by different time-givers. A recent article in this newsletter introduced our research on alternatives to the clock. In this one, I go into depth about time-givers: what they are, how they structure our lives, and some examples — from the mundane to the more extreme.

Who’s your pusher?

The term “time-giver” comes from the German word Zeitgeber, coined by chronobiologist Jürgen Aschoff. Between the 1960s and 1980s, he sent more than 400 people (mostly students — welcome to academia!) to live for a few weeks at a time in a bunker inside a Bavarian mountain, shielded against every possible external time cue: light, sound, vibrations, electromagnetic variations. Aschoff and his colleagues monitored various biological functions as well as their psychological wellbeing.

Schmid reports in her PhD research: “After a short period of adaptation at the beginning of the experiment, most of the participants described the isolation as a very productive time,” and some even expressed the desire to stay longer in isolation.

And this was before smartphones, social media and any need for “digital detox”.

In chronobiology, Zeitgeber is now a commonly used term. It describes entrainment signals, which cause “an impulse for a biological oscillator to react and synchronise to external rhythms,” Schmid writes.

She illustrates this herself, sitting in a swing. On the right in the image, you can see someone pushing her — that pusher is the Zeitgeber, setting the oscillating rhythm. Of course Schmid herself also has a role in moving the swing, just as we have some control over the rhythms we live by. We can set our own rhythm just by using our body, without any external pusher. Or we can combine the pusher’s motion with our own bodily movement. But if the pusher pushes at the wrong moment, or the swinger’s movement doesn’t match the pusher’s, things get out of sync.

In Schmid’s research, the Zeitgeber is part of her way of getting you to unlearn time. Thinking in terms of time-givers instead of clock times “follows a more holistic approach,” she writes, “by shifting the perspective to a number of forces that influence people’s perception of time.”

Following the crowd

Time-givers can be divided into natural, societal and bodily. The natural ones most people know: light (primarily the day/night cycle), lunar cycles, the seasons. These all still influence most people, and other living things.

It’s easy to see how these became societal time-givers: work shifts, calendar months, planting and harvest times. It’s also easy to see why increasingly precise social synchronisation mechanisms like the clock were introduced: to sync up the activities of increasingly large and spread out groups of people. Work and school times, meal times and market days all became strong time-givers.

It’s equally easy to see how clock times can become desynchronised from those natural time-givers, when they become tied more to societal than natural rhythms. Human groups of any size come with power relations.

Alongside these fairly strict, event-driven time-givers, the rhythm of the human day gave rise to more informal ones, like commute periods, personal and family rituals. Reliance on other individuals as time-givers presumably predates humans, because we can observe it in many other species. It can range from, for example, moving only as fast as the individual in front of you, to moving with the crowd.

A participant in an experiment we ran used the sound of urban rhythms to structure her day. She categorised the sounds she heard throughout the day into natural (birds, wind), societal (construction work, church bells) and bodily (people talking, footsteps). Then she used these to structure her own work, divided into analog (drawing, reading), digital (using a laptop), and “maintenance” (cleaning, eating, sleeping) respectively.

“It sounds strange’, she told us, “but these sounds help me to work. It makes me think I have to work because others are working. But this is maybe too much because of the clock-time society.”

Unsurprisingly, there were a lot of work-related sounds during weekdays, and these sounds were more frequent, so she had to divide her tasks into small chunks. During weekends, birdsong and calm voices made for a slower rhythm and, for her, different types of activity.

Needless to say, the experiment raised the student’s awareness of her surrounding environment. “Working digitally, I was typing harder when drilling noises were too loud. Working analogue, I tried to listen to bird sounds. Some sounds were pleasant to listen to, while other weren’t and I would try to block them out. This is reflected in the activity.”

But, importantly: “For some reason, my concentration became better. I realised not visually seeing the passing of time made me focus more on the essential and made me enter a flow state, where I forgot to listen to what was happening around me.”

Time dictators

Societal time-givers overlap with bodily ones when we rely on other people as time-givers. Anyone with children knows this well: hunger, tiredness, the need for a bathroom can hardly be avoided. Same goes for pets. And anyone who lives with a partner will tend to synchronise your rhythms, in order to eat, sleep and socialise together.

One of Schmid’s students tried synchronising with a remote partner’s rhythms. As an added wrinkle, the partner was in a different country and time zone. So the student’s sleeping and eating times shifted by an hour, for a start. His partner was a professional dancer, so he spent an unusual (for him) amount of time dancing. During dinner, she accidentally poured too much hot sauce on her dinner, and in order to live the same life, he did the same. Too much synchrony?

Another participant in our experiment took a different approach and asked someone else to explicitly tell her what activities to do and when. She first covered her windows so as not to be influenced by natural light, then asked her designated time-giver to dictate occasional tasks; the rest of the time, she went about her normal activities. She reported:

Very quickly I entered into a state of drowsiness. I felt tired and very relaxed. I slept a lot and upon waking felt very much connected to my inner self. I totally lost count of time, it is interesting how quickly we adapt to a new rhythm. This new state of being actually gave me a lot of new inspiration. I started to question our time system and how we live according to it.

Time to eat

Hunger is such a strong time-giver, a group of Schmid’s students used this as their main time-giver: “We will let our stomachs tell the time,” they wrote in a manifesto. But they also combined this with music. This is the strategy of doing what you enjoy, when being given the time and freedom to do so. In their case, cooking, eating and listening to music all the time. They still stuck to the three standard mealtimes of breakfast, lunch and dinner. But they treated the music as both an “ingredient” in their cooking, and as a measuring device: the search for a perfectly cooked egg yielded Miles Davis’ “So What”. (Good taste in music, but at nine minutes, that sounds like an overcooked egg to me).

Schmid herself has used food as an alternate time-giver in her teaching. Students might have to present their work in the time it takes for their classmates to drink a small bottle of juice. Or, if they present within a certain time period, they might receive a piece of cake as a reward (and Schmid is a top-notch baker).

More generally, in her research, Schmid has developed daily bodily phases as time-givers. You can read about these in her book, or in this article we wrote together.

Another student group developed costumes with bells and other sound-producing devices, to turn each bodily activity into sound: active phases were noisy, sleep time was quiet. This is the opposite of a time-giver, recording when the body does what.

Going outside

Looping back to the time-giving cat, it shows how classifying time-givers as natural, societal or bodily is rarely clear-cut. The cat is at once natural, societal (in terms of pet ownership), and bodily (the cat’s, that is).

But there are other time-givers that don’t fit into any of those categories. Because Schmid works primarily with artists and designers, their responses tend to be pretty creative. This is why we find artistic research to be more interesting than scientific experiments. Instead of a science student quietly reading in an underground bunker, why not a student reading on a busy sidewalk?

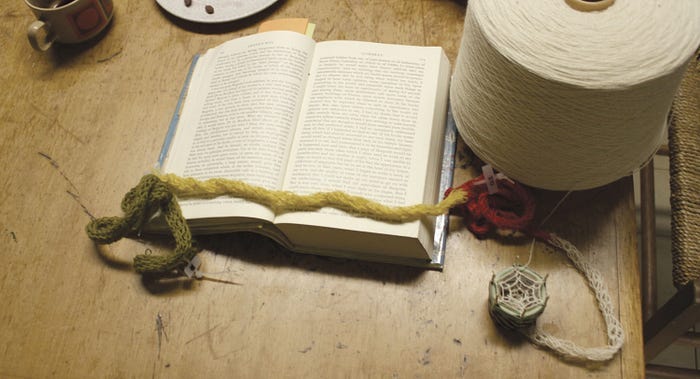

Reading was actually another time-giver chosen by a student group. Specifically, reading Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, appropriately. Each person read a chapter aloud, while the others slept, ate or — as a form of timekeeping — knitted a long strand, each colour of yarn representing a different person. (Such a form of documentation beats a diary by a long way.) Social, yes, but not societal, nor natural or bodily.

Similarly, another group turned their conversations and activities into threads to create a large a large net. Each person was represented by a strand, and their interactions were woven together, making the connection between “net” and “network” explicit.

Then there was the more technically-minded group who created an electronic timer that operated at completely random times. Your time to eat or sleep, for example, could range from five minutes to five hours. Closer to the cat’s rhythms, but far from natural.

Space as time

How about space as time-giver? This is part of Schmid’s research — she designs spaces matched to the bodily phases of the day that she developed. Most of us have purpose-built rooms for eating and sleeping, but what about one optimised for cognitive activity, or creative work?

The student who used external sounds as time-givers ended up incorporating space into her experiment: moving between different rooms, she could modulate different types of sounds coming from different sources.

In Schmid’s experiments, space also plays a key role. Schmid sends groups to the most unusual places she can find, to enact their chosen time-giver. The hunger group was sent to a converted pumping station just outside London. The Proust group was in an old library. The net group, in a big barn.

The weirdest, though, was the Pink House.

Officially known as Eaton House Studio, it is quite literally a large house painted a custom shade of pink, in the part of the UK known as Essex. Inside is more pink, plus some neon, a fair number of hearts of various sizes and materials, zebra stripes, fake fur… I could go on (or you can Google it).

So the students decided to use the space itself as time-giver. Individually, they spent time in each of the house’s many rooms, until they simply couldn’t take it anymore. Use of the many bedrooms led to, as Schmid describes, “a polyphasic sleep pattern, in contrast to our societal day-and-night rhythm (monophasic sleep pattern).” She explains:

The psychiatrist Tom Wehr suggests that the natural sleep of human beings shows a biphasic pattern, in contrast to the monophasic pattern today’s society so strongly believes in. In one of his studies, electric light, or rather a lack of it, was the focus of an experiment conducted in 1990. He asked volunteers to live their regular lives, only without modern light sources. In the winter months, when the experiment was carried out, the participants’ daily routine was limited to the daylight hours. As in the premodern era, the twelve or more hours of darkness were no longer perceived as an “active” timeframe. After recovering from a chronic sleep depth in the first month, subjects slept an average of eight hours a night, separated in to two segments (biphasic sleep). It would seem that the homeorhythmic pattern of sleep has been overwritten by the societal concept of monophasic sleep, probably to fit better into an efficiency-driven world.

Sleep patterns aside, the students were pretty freaked out by the place. Having space dictate time can be liberating, or suffocating.

And so with all time-givers. It’s not for nothing that the wristwatch was once called “the little slavedriver”. The notion of entrainment most often comes down to training people to exist in capitalist society.

Taking control of your time-givers, is therefore key to unlearning clock time. Don’t forget the social aspects of time-givers. Do forget about “taking time” or “saving time”, and think instead about giving time.

You can read more about one of our time-giver experiments here.

Love all of this - extra because it brings to mind my favourite word ever, since cats are ~*crepuscular*~ (most active at dusk and dawn)